bücking&kröger

Stefan Eichhorn

Fabian Reimann

Florian Rynkowski

Technocracy was a significant social utopia in Northern America during the early 20th century. Many demands of Technocracy Inc., founded in New York in 1920, seem even more relevant today than back then: unconditional basic income, 4-day week, prosperity for all, widespread resource-conservation, abolition of money.

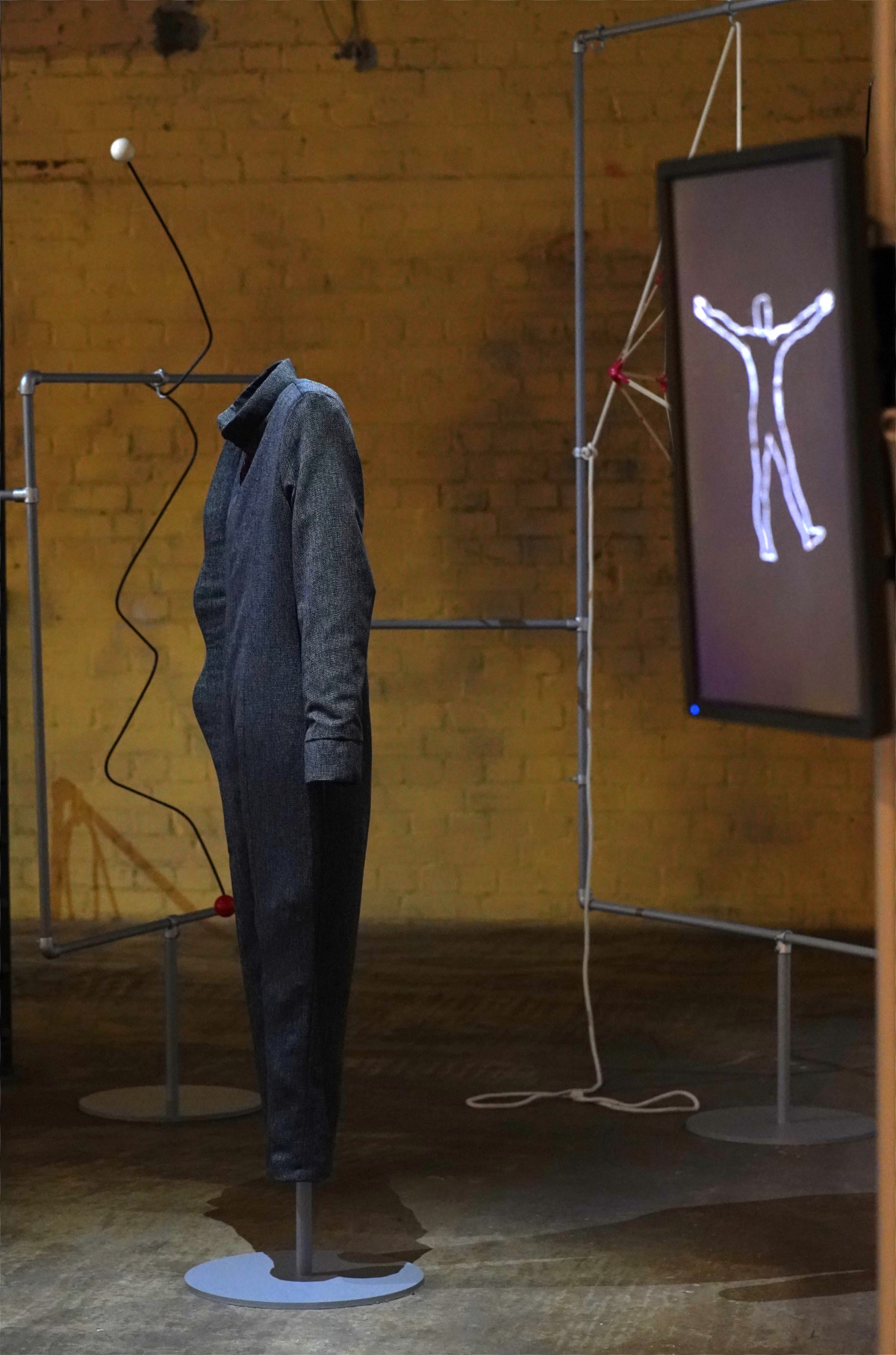

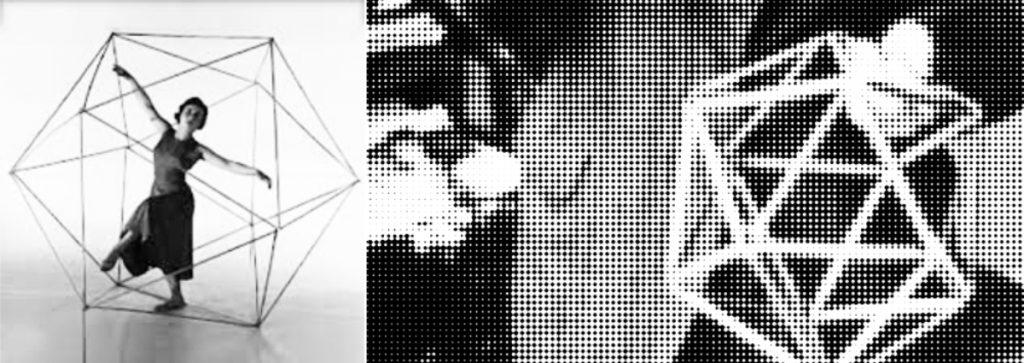

This exhibition reconstructs the now almost unknown stage play »technocrats« from the few surviving materials: choreography, music, costume and stage design. One can see how movements based on the analyses of contemporary work processes were transformed into choreography.

2024

There is this statement on the creation of the piece “technocrats”, which has been translated and re-recorded. (7:55 minutes)

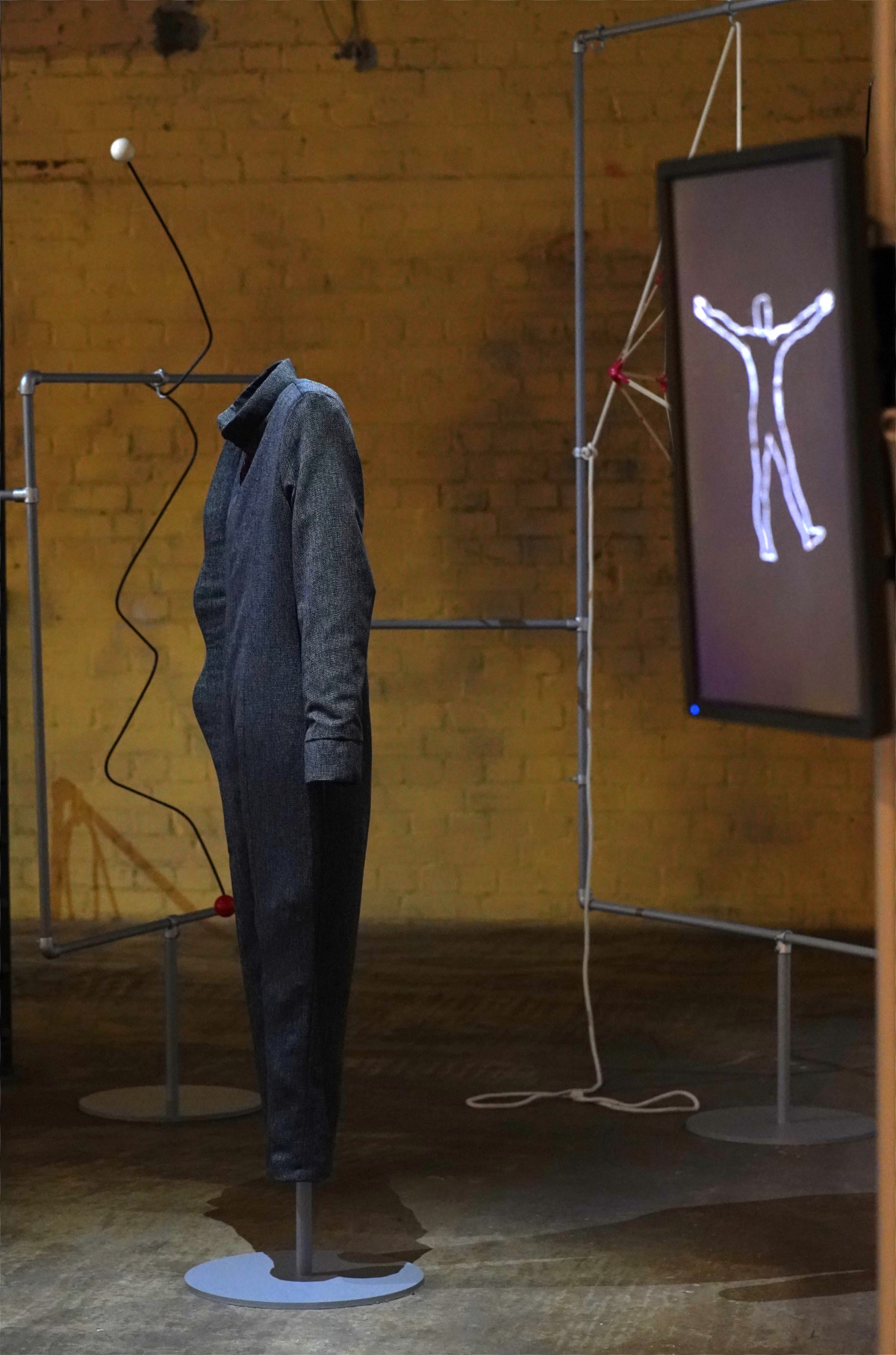

Egon Eiermann is regarded as one of the designers who re-established the modernist design tradition in West Germany after the Second World War. A table from 1953, a construction made from a few round tubes, became a modern classic. Like few other pieces of furniture, the Eiermann table symbolises rationality and engineering spirit. The world-famous model is the lightweight version by Adam Wieland.

Here, the raised version with a large grid is a display in the exhibition.

The core theses of the technocracy movement were summarised in a series of 80 images, which are presented here in digital reconstructio

Two large black metal rings connected by six metal rods, together with a few brackets and two small metal surfaces, form what is known as rhönrad. This piece of sports equipment was developed by Otto Feick and patented in 1925. It quickly became very popular. Its inventor presented it in the USA in 1929. Some members of technocracy inc. probably attended a presentation of the wheel.

The technocrats’ interest in the rhönrad can be explained by the shape and measurement of the human body. This double effect is linked to the first written and dimension-defining representations, the world-famous Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci and, remotely, the writings of Albrecht Dürer.

In this case, measurement and staging are more synchronised than in any other sporting discipline. Da Vinci, Dürer and the patent are mixed in the video.

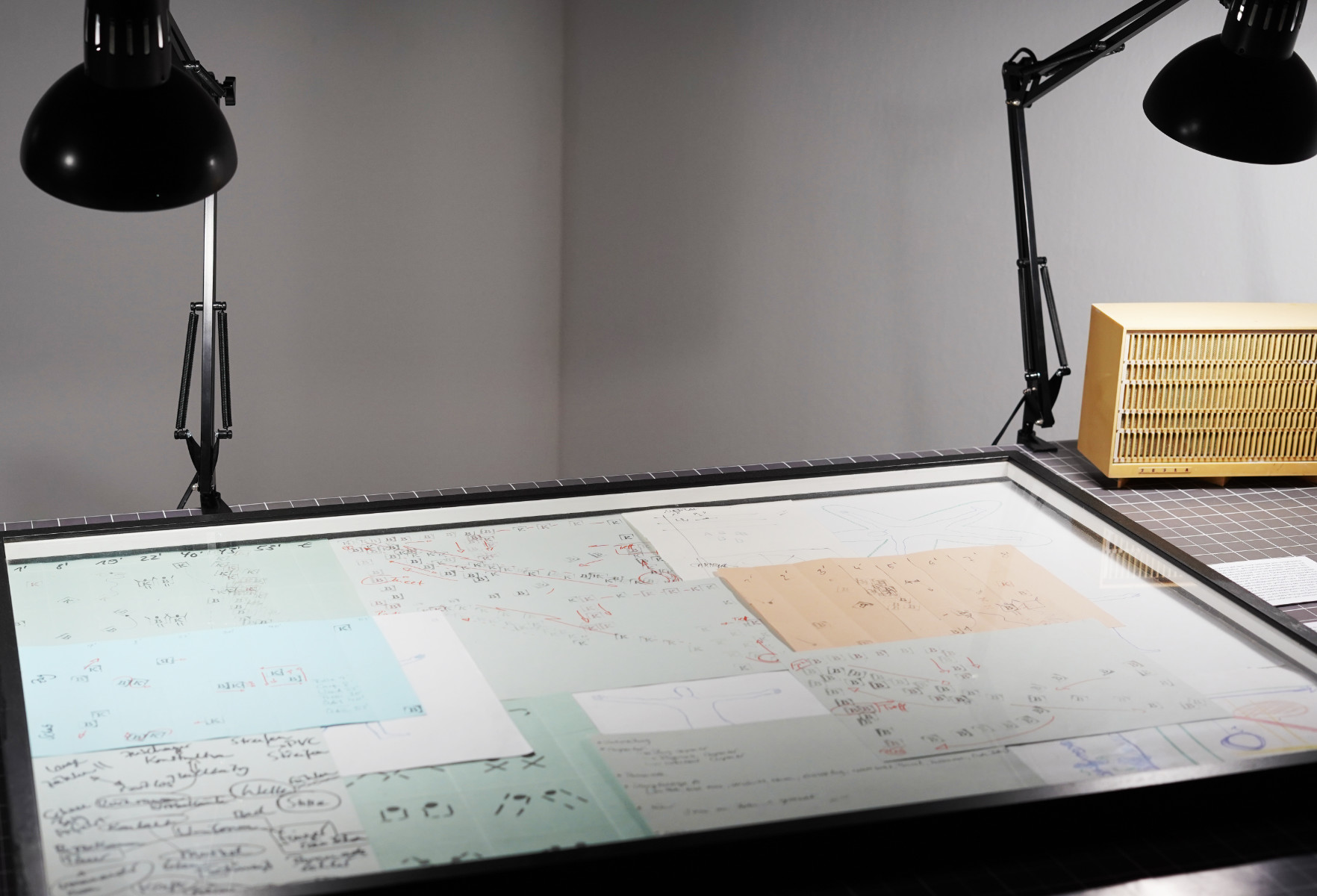

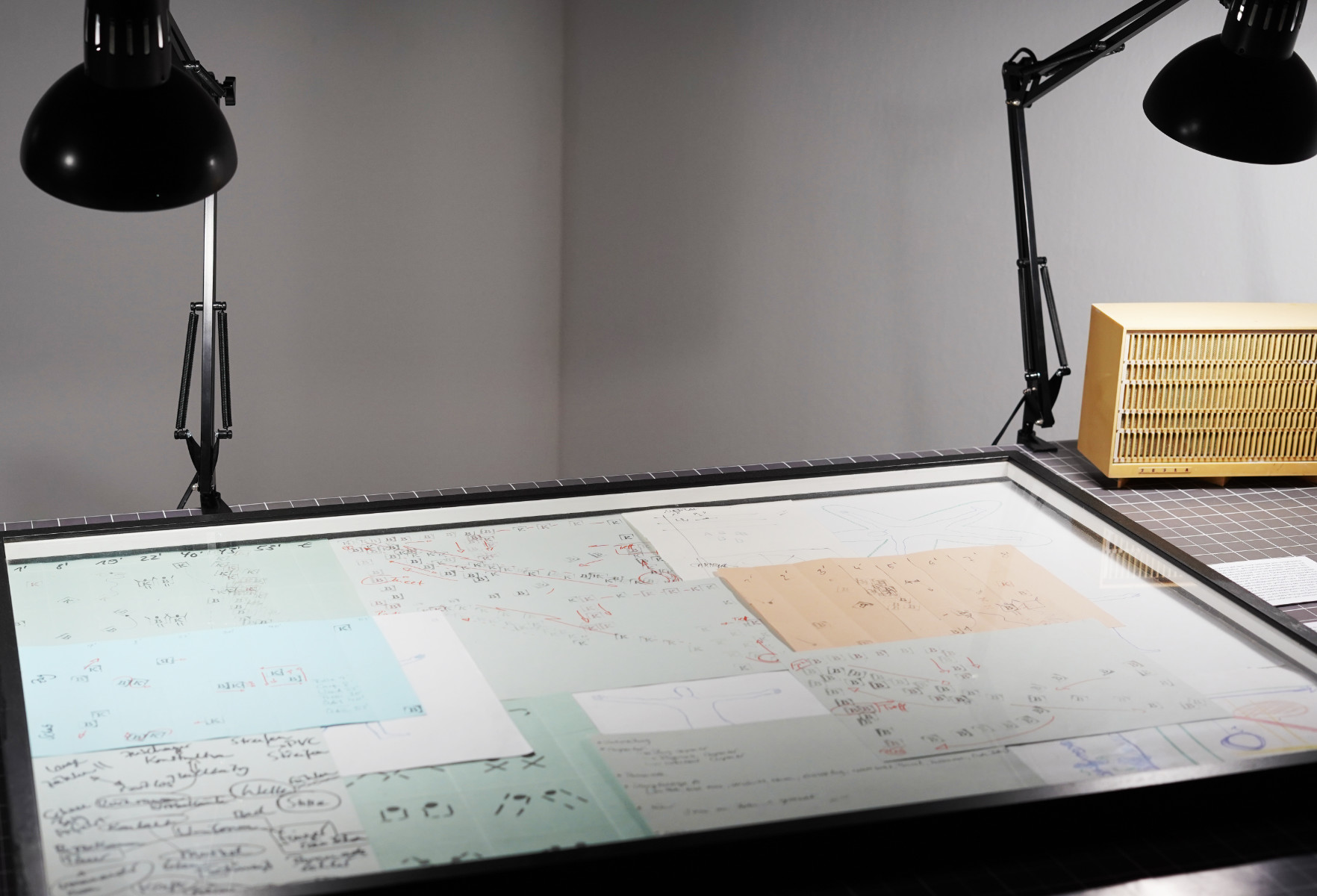

In the display case on the table there are several sheets of dance notation, which were used to reconstruct the images, scenes and sequences of the piece. Until the end, it was not possible to clarify whether it was merely a dance performance or whether it was also a form of practice for technical councillors. Words and text fragments found suggest that there is a larger philosophical concept behind the performance, which translates technocratic theory into body movements. Concepts such as energy generation, thrust or pull could have been removed from their existence as a mental construct and experienced and internalised physically on a daily / regular basis by means of exercises.

The grey frames, which are on the identical object holders of the exhibition display, show studies and patterns of moving.

The grey frames, which are on the identical object holders of the exhibition display, show studies and patterns of moving.

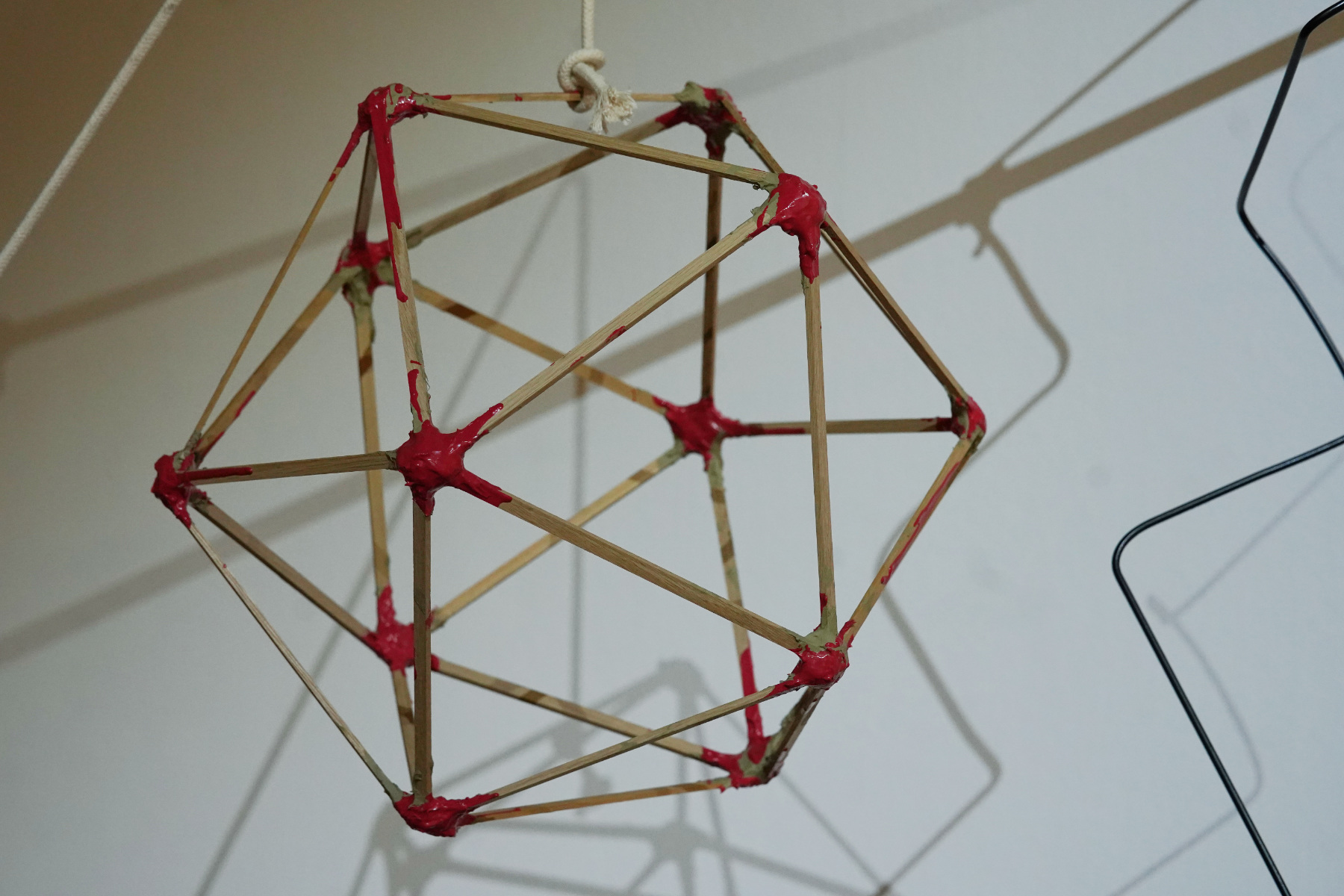

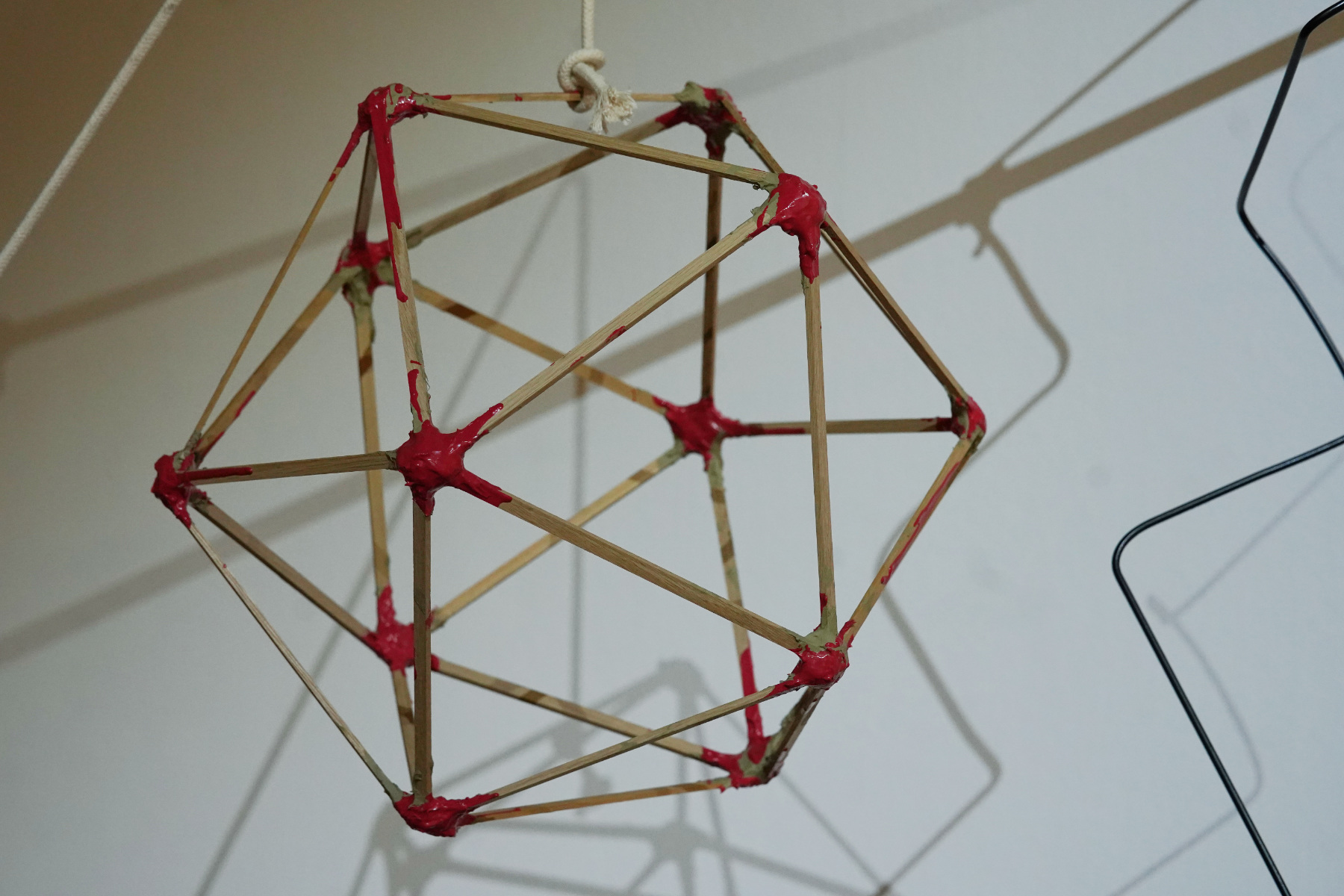

The wooden rings, whose purpose was to be used for “early childhood physical education”, have been assembled into a rudimentary globe. They would be maximum extensions of the movement space. This slightly compressed ball could be a reference to the depiction of Vitruvian man. This expansive realisation finds its continuation in an isocahedron.

The dancer and dance theorist Rudolf von Laban, a pioneer of modern dance, chose this form to use points of movement in a three-dimensional object in dance training.

Upward and downward movements are drawn in the air between coloured spheres.

The book The World Set Free contains the complete 1912 novel by Herbert George Wells and has been expanded to include a pictorial essay that interprets

the text’s predictions for the future.

In the 1920s, Wells was a world-famous author, a founder of the entire genre of science fiction, as

Mark von Schlegell writes. The chapters describing

the abolition of money in favour of a value creation system based on the availability of energy are certainly of particular interest to the technocracy movement.

The score fragments on display here resemble circuit diagrams. In a thoroughly optimised society, circuit diagrams could also serve as organigrams of larger social contexts; here they are musical playing instructions.

Unfortunately, no reliable information about the original instrumentation has survived. The work therefore conjugates various plausible possibilities. Acoustically generated sounds, sound synthesis and sampling technology are used.

The reconstruction of a larger section of technocratic art music from individual fragments shown here is thanks to the Lachhab method. It was actually developed by geophysicist Ahmed Lachhab to restore ancient Roman mosaics using geophysical knowledge.

Despite its seemingly purely functional design, the reconstruction allows for further interpretations on closer inspection. For example, it is probably possible to deduce intended poetic motifs or therapeutic potential.

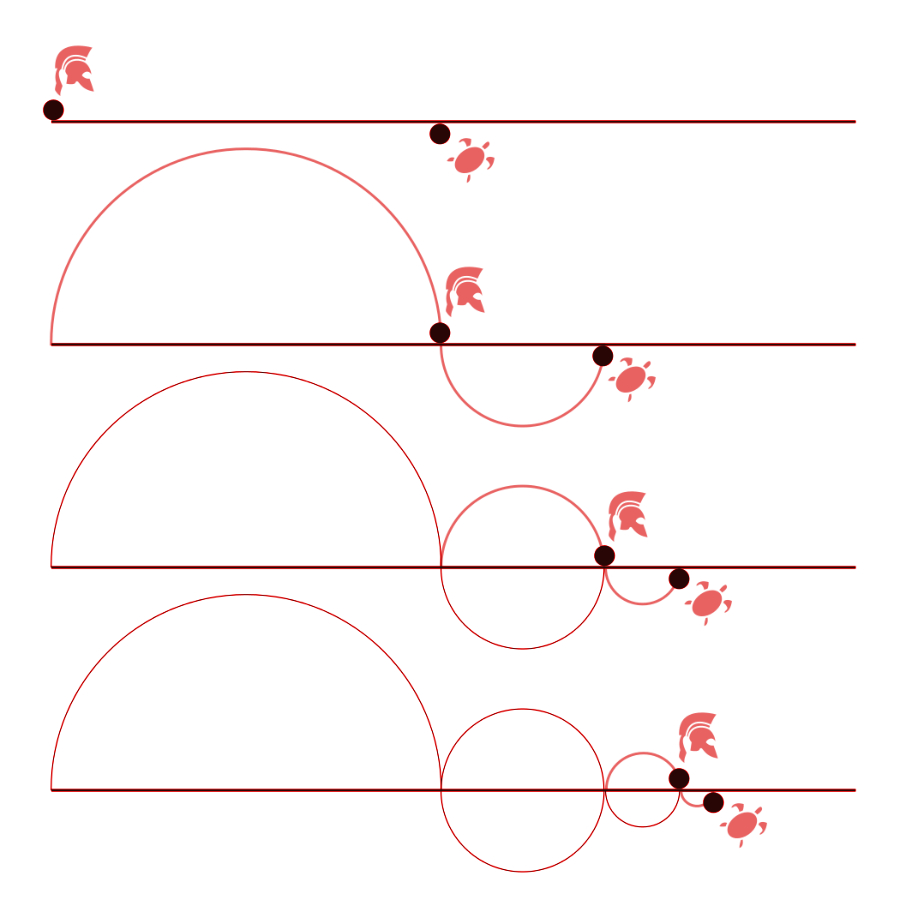

The uniform of a utopian movement combines elegance and treacherous functionality in a dark gray tweed overall that wraps its wearer in a timeless aesthetic. Inspired by costumes from science fiction films of decades past, the jumpsuit exudes a mixture of retro-futurism and modern design. A closer look reveals another detail: the red lining is decorated with a drawing that alludes to the philosophical paradox of Achilles and the tortoise. This describes a seemingly insurmountable contradiction in which the faster runner Achilles gives his slower competitor, the tortoise, a head start. Although Achilles is much faster, he never seems to catch up with the tortoise, as he only ever reaches the point where the tortoise was before him, leaving an infinitesimal time difference. The paradox serves here as an allegorical image for an utopia in which, despite constant progress and individual abilities, new horizons are constantly being conquered without ever reaching the perfection of an ideal society.